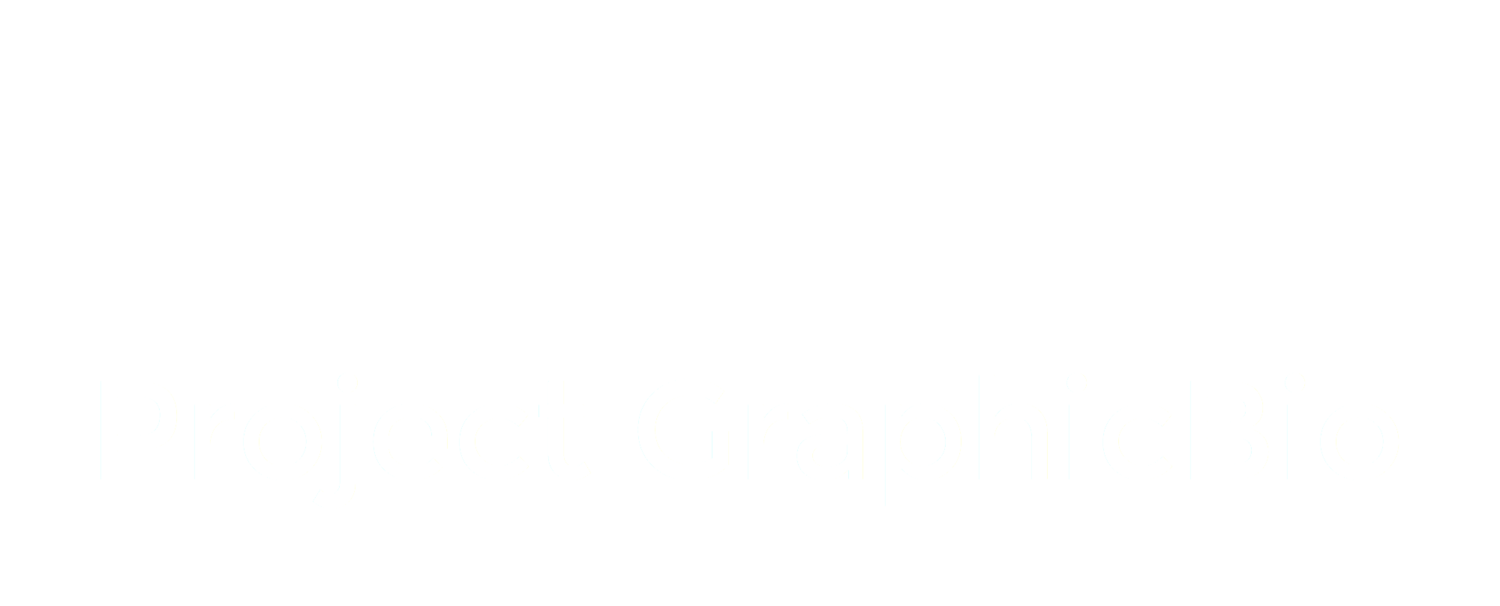

Guest Post: Jessica Fontaine Reviews Who is Ana Mendieta? by Redfern & Caron

Embodying Ana Mendieta: A Review of Who is Ana Mendieta?

Jessica Fontaine, Research Assistant

In Who is Ana Mendieta?, Christine Redfern and Caro Caron reanimate the life and work of Cuban American artist, Ana Mendieta. Published in 2011 by The Feminist Press, Who is Ana Mendieta? introduces readers not only to Mendieta, but also to the feminist performance art movement of the 1970s and surrounding issues of sexism and violence that Mendieta took up in her work.

Redfern narrates Mendieta’s biography in two parts: a mash-up comic and an annotated bibliography entitled “Blindspot”. The mash-up comic moves like a biopic, placing the reader in contact with an extensive cast of characters from the 1970s New York art scene. As the eyes of the reader move over Caron’s large, crowded, gray and black toned panels, Mendieta and the re-imaginings of her performances press up against the artists, curators, and critics who informed or challenged her career. Redfern carefully chooses their dialogue and the narration from articles, reviews, and accounts, giving the comic a documentary feel. The following newspaper-styled bibliography acts like footnotes. It allows Redfern to explicate the comic’s short narrative and further illuminate how Mendieta’s work confronted the very frameworks of sexism that led to her violent death.

Inseparable from the story of her life and art is the suspicious way Mendieta died, falling from the 34th floor of her New York apartment building in 1985. Both Redfern’s narrative and Caron’s illustrations draw connections between Mendieta’s focus on the body and the earth as artistic mediums and Mendieta’s broken body crushed against a concrete roof.

In the depiction of her death, Caron’s drawing of a Mendieta “Silueta” stands equally beside her picture of Mendieta’s lifeless body. A boxed narration accompanies the images and muses that Mendieta’s death was “an eerie echo of a 1973 ‘Silueta.’” Mendieta appears ripped from nature, the site of many of her sculptures and means of performance, and thrown into the urban public, a masculine space of violence. This “Silueta” is the last of multiple recreations that fill and focus the comic’s panels on Mendieta’s physical shape. Such a severe end to these recreations highlights not only the “Silueta’s”series’ performative and corporeal natures, but also gives Redfern space to examine how Mendieta’s art and legacy has been mistreated within the avant-garde art world.

In the “Blindspot” bibliography that follows the comic, Redfern points systematically to the incommensurate ways violence awards myth and legend to male artists, such as Pollack and Warhol, while it amputates the artistic reach and lives of women. She is unapologetic in pointing to the inconsistencies in the testimonies of Mendieta’s husband, Carl Andre, who was in their apartment at the time of Mendieta’s death. Further, Redfern’s varied collected sources, displayed together, protest against the ways institutionalized and social powers work to maintain these inequalities. On a broader level, the bibliography and comic reiterate the feminist project of demonstrating how the personal is political. For Who is Ana Mendieta? specifically, the repetition of embodying simultaneously Mendieta’s image and art resurrects Ana Mendieta for a new generation and continues protests against the way she and other female artists have been neglected within the arts canon.

See images from the book at the Caro Caron + Christine Redfern page of the Concordia University Faculty of Fine Arts web site.